River History

The Quinipiac River headwaters form at the Deadwood Swamp on the New Britain-Farmington border. The river then meanders south for 38 miles, through Meriden and Wallingford, and ultimately drains into New Haven Harbor and Long Island Sound.

By the Numbers:

- 38 miles long

- 165 square mile watershed

- Travels through 14 municipalities

- 913 acres of tidal marsh

- 20 tributaries

Geological Formation

The Quinnipiac River as we know it today began forming at the close of the last ice age, about 21,000 years ago. As the mile-thick glaciers that had blanketed much of the Northern Hemisphere retreated, they deposited a mix of rocks, and course gravel, and soils – known as till – on the hills. The finer gravel, sands, and clays filled the valleys and formed the beds to a series of glacial lakes created by the melting ice. The lake that was the precursor to the Quinnipiac lasted for approximately 400 years until water pressure from the glacial melt eventually forced open channel to Long Island Sound.

First Inhabitants

Roughly translated, “Quinnipiac” means “long water land,” a name given by the Algonquin tribes who lived along the river for centuries before European arrival. The tribes were experienced in planting corn, hunting with spears, and fishing. They also harvested the abundant oysters on the Quinnipiac, as evidenced by mounds of oyster shells they left along the banks.

European Settlement

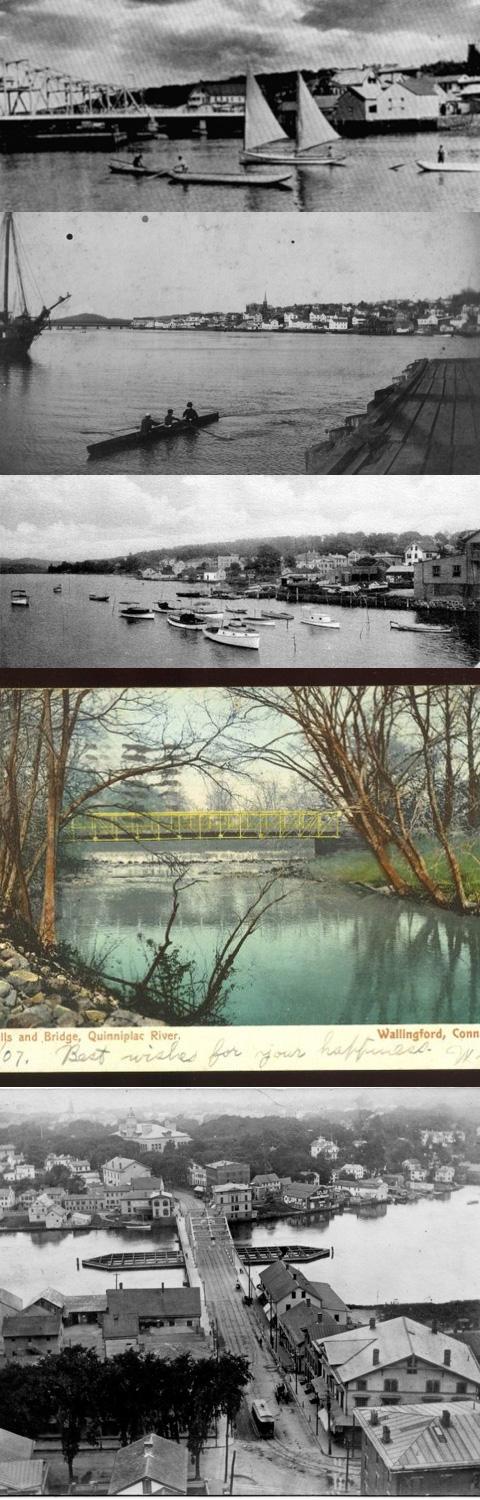

Europeans first arrived to the area in 1614 and immediately recognized the value of the river’s abundant fish and oysters. By the late 18th century, numerous fishing huts, farms and homes had sprung up on both sides of the river. As in most of New England, timber harvesting and farming radically transformed the environment along the river.

Settlers and sailors called the lower river “Dragon,” named after the large population of harbor seals they called “sea dragons.” With its rich oyster beds and river port, the area of Fair Haven began to prosper. Oysters were used, not only as a food source, but also as a commodity; their shells used for fertilizer, road lining and decoration. Oyster operations became the community’s lifeblood, and, in the early 1800s, earned it the nickname “Clamtown”. Few knew, at that time, just how important the oysters really were - specifically their value to the river’s health as natural filters and purifiers.

Industrialization

By the 1850s, rapid advancements in hydro-powered manufacturing brought industry to the Quinnipiac’s shores. On the upper river, Meriden and Wallingford became world renowned producers of silver-plaiting and metal ware, and their populations rapidly expanded. Other cities and towns along the Quinnipiac also grew, and the river soon became severely polluted with the direct discharge from factories and municipal sewer systems.

In 1886, the Connecticut Legislature passed the state's first-ever pollution control measure to try to clean up the Quinnipiac, and banned the City of Meriden from discharging sewage into the river. But heavy industry, leaching garbage dumps, and continued residential development up and down the river devastated the water quality.

The once-fertile oyster beds at the river mouth became inundated with sediment, related pollution and diseases. By the early decades of the 20th century, Fair Haven’s once thriving oyster industry had all but vanished, and most of the fish had also disappeared from the river’s mouth.

The river remained highly toxic for much of the 20th century. The Connecticut Clean Water Act of 1967 and the Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 both led to vast improvements for all water bodies, including the Quinnipiac. Urban renewal in the 70s and 80s spurred the removal of many water-polluting businesses and the creation of parks along the river’s edge.

Today, the Quinnipiac River is slowly beginning to recover from the years of pollution. Fish have returned to the river, and oysters, an indicator or river health, are making a strong recovery. Oysters continue to be seeded and harvested in the traditional method. New techniques in aquaculture, such as growing oysters in floating beds, are also being explored on the river.